Chromatin and Histones

The basic building block of chromatin is the nucleosome, which contains 147 base pairs (bp) of DNA wrapped in a left-handed superhelix 1.7 times around a core histone octamer (two copies each of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4). Each core histone contains two separate functional domains: a signature “histone-fold” motif sufficient for both histone-histone and histone-DNA contacts within the nucleosome, and NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal “tail” domains that contain sites for posttranslational modifications (such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination). Although these histone tails are mostly unresolved in the crystal structure of the nucleosome, they appear to emanate radially from the nucleosome, conveniently positioned to associate with “linker” DNA residing between nucleosomes or with adjacent nucleosomes.

In addition to the core histones, metazoan chromatin also contains linker histones (such as histone H1), which bind to nucleosomes and protect an additional ~20 bp of DNA from nuclease digestion at the core particle boundary. Linker histones are not related in sequence to the core histones, but they also contain a globular domain flanked by NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal tail domains. Although only the linker histone globular domain is essential for binding to nucleosomes, the tail domains are believed to be important for linker histone roles in chromatin folding.

Histones

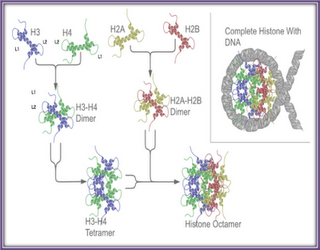

Histone proteins are among the most highly conserved proteins of higher eukaryotes. Their status as such is reveling as to the importance of Histones both structurally and functionally to the cell. Mutations within the Histones are simply not tolerated, as the fine structure and balance of charge are critical to their functions. In Eukaryotic cells there are 5 main Histone proteins, a linker Histone H1, and the four core Histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. These proteins are extensively posttraslationally modified, particularly on their unstructured N termini tails. Histones are by far the most abundant DNA associated protein. Consistent with this role Histones have a high content of positively charged amino acids, where about 20% of all residues are either a Lysine or an Arginine. The core Histones is also relatively small protein ranging in size from 11 kDa to 15 kDa, while H1 is about 21 kDa. A Conserved region is found in each of the core Histones called the Histone fold domain, which is composed of three alpha helices separated by two unstructured loops. It is this domain that mediates the formation of the Histone core particle. Two heterodimers of H3 and H4 come together for form a tetramer core, which makes contacts with DNA. The core particle is then completed by the addition of two H2A H2B dimers. The core Histones each has an unstructured amino terminal tail. These tails are not required for DNA to contact the Histone octamer, but are instead the sites of extensive posttranslational modifications, which alter the function of the individual nucleosome.

Nucleosomes and the 10 nm fiber. DNA is wound around this octamer approximately twice (~147bp) to achieve a packing ratio of about 6. Though this is a considerable increase in packing it is still not enough. Interphase nuclei have a packing ratio of about 1000- 2000, while metaphase chromosomes have a packing ratio ~ 7000.

DNA forms higher order structures. The primary level of organization can be described as appearing as like beads on a string or the basic unit fiber. A nucleoprotein is a complex of associated DNA with its own mass in basic histone proteins, and almost the same mass in less basic non-histone proteins. Histone proteins are highly conserved in many species. The nucleosome (a nucleoprotein) is about 2 turns of DNA wound around a histone core and plays a central role in the packing of DNA into the nucleus and is the primary determinant of DNA accessibility. When DNA is wrapped around the nucleosome DNA that is associated with the nucleosome is less susceptible to DNase digestion.

When DNA is replicated the new strands are quickly wrapped into nucleosomes after the replication fork passes by special nucleosome assembly proteins. They wrap the DNA around the H3 H4 tetramer; insert the H2a and H2b units to complete the octomer so that the nucleosome exhibits dyad symmetry. Statistically there seems to be a preference for the AT rich minor groves to face the histone octamer, each of the heterodimers contacts about 30 bp of DNA. Arginine side chains face into all the minor groves to maintain rigidity. There are roughly 14 turns of the DNA helix around the nucleosome, because some twisting of the helix is induced by the octamer in the middle of the coil around the nucleosome. H1 histone acts a brace for the octomer, clipping it all together. About 15 to 55bp of linker DNA is between each nucleosome. This can be seen visually under a microscope in low salt concentrations as a ‘bead on a string’ like appearance. This is the primary structure of chromatin or the basic unit fiber.

To investigate the structure of the nucleosome further scientists used the property that the DNA wrapped around the histone octamer was less susceptible to nuclease degradation than the exposed linker DNA between the subunits. This allowed researchers to isolate and resolve the fine structure of the histone octamer. When the nucleosome is digested with a micrococcal nuclease that digests the linker DNA and releases a 166bp chromatosome (the nucleosome minus the linker DNA) and then can be further digested to remove the H1 subunit and to release the nucleosome core particle. When the crystal structure of the histone octamer is examined the octamer is confirmed to be a flat disc. Each of the 4 histone proteins share the conserved helix turn helix turn helix motif (α1, L1, α2, L2, α3) called the central histone fold domain. Heterodimers form so that there is a juxtaposition of the L1 and L2 of each of the proteins creating a tapered appearance. Each histone has both C and N terminus unstructured tails that make up about 28% of the mass of the core. These tails are subject to posttranslational modifications that allow a cell to regulate how condensed the chromatin is, and how able it is to form higher order structures.

The DNA path around the histone core is not a completely uniform path and a considerable amount of variation is seen depending on the superhelixal state of the DNA. The nucleosome causes the DNA to become over wound so that there are 10.2bp per turn. This is because it allows the minor groves and major groves to line up forming channels that the histone tails can pass through, and leaving the major groves accessible to DNA binding proteins to allow the DNA to partake in normal cellular process. But for most interaction with DNA then DNA needs to disassociate from the histone octamer. Dissociation occurs in semi cooperative stages where first the H3 terminals where the DNA enters and leaves the nucleosome dissociate which then induces dissociation in the H2A and H2B heterodimers followed by the H3 H4 heterodimers. I would like to hazard a guess as to how DNA binding proteins could cause the nucleosome to disassociate from the DNA. The increased acetylation disrupts the higher order structure of the chromatin allowing DNA binding proteins to move in to these areas. Because 4 of the 14 minor groves have H3 histone tails passing through them, and H3 tails also contact the DNA as it enters and exits the nucleosome, I guess that when a DNA binding protein binds with a strong association to a promoter region that this induces some kind of conformational change into the H3 tail and thus induces the disassociation event. I have found no literature on this and don’t know weather this has been tested, proved or disproved. If I had a lab and all the skills in the world I would test to see if those regions that bind to DNA binding proteins are statistically associated with the H3 tail passing through the opposite grove on the nucleosome. This would be a preliminary test to see if in fact this could be an explanation. A further thought on this is that the H4 tails makes many contacts with the H2A H2B heterodimers of a neighboring nucleosome core, and this could be away of transferring conformational information from one nucleosome to the next. I am aware that there are nucleosome remolding proteins but have had little time to read up about these things. This was just a thought exercise.

Increased acetylating of the histone tails has been associated with transcription activity and the reverse for repression. One view is that the net charge reduction caused by acetylation causes the conformational change in the nucleosome. Histone tails interact with neighboring nucleosomes and linker DNA and control the amount of condensation of the chromatin. Tails can undergo reversible acetylation on specific amino acids on the tails; this decreases the net charge and thus decreases the interaction with the negatively charged DNA. Increased methylation of tails is associated with prevention of acetylation thus the nucleosomes are more likely to form the 2ndary level of structure.

H1 and the 30 nm Fiber

Chromatin forms a 30 nm fiber under the microscope. There are two models for the structure of this fiber, the solenoid model and the Zigzag model.

Under the Solenoid model each coil has about 6 nucleosomes per turn (and therefore contains about ~6*~200bp) to form a 30nm fiber. H1 histone slots in on the inside of the solenoid and is bound to the DNA locking the nucleosome in place. Electron microscopy suggests that the 30 nm fiber is not quite a perfect solenoid it may be a loose helical structure.

The crystal structure of the tetranulcosome has been resolved to show that the linker DNA may zigzag backwards and forwards between the nucleosomes.

Histone H1 is less conserved than the other core histones, and has 5 different variants in mammalian genomes, each of whom have different roles gene regulation. H1 facilitates the higher order packing of chromatin, by binding to the linker DNA and maintaining the correct spacing between the nucleosomes. High levels of H1 proteins are associated with the formation of the 30nm fiber and also with a decrease in gene activity. The converse is also true, low levels of the H1 are associated with gene activity. The secondary structure is a dynamic structure and must be able to partially unfold and refold to this solenoid form

Histone Tails are required for the 30nm Fiber

Core histones that lack the amino terminal tail are incapable to forming 30nm fibers. The most likely role of the tails is to stabilize the 30nm fiber by interacting with adjacent nucleosomes. This model is supported by three dimensional crystal structure of the nucleosome, which shows that each of the N terminal tails of H2A H3 and H4 interacts with the adjacent nucleosome. Recent studies indicate that the interaction between the positively charged N termini of H4 and negative charged region of the histone fold domain of H2A is extremely important for the formation of 30nm fibers.

Chromonema Fibers

What is the structure of the chromatin fiber in vivo? Do 10-nm, bead-on-a-string chromatin fibers exist, or are they only present in vitro in low-ionic-strength environments? In vitro, the concentration of divalent ions required to induce 30-nm fiber formation is really quite modest (1 to 2 mM). In fact, the estimated Interphase nuclear concentrations of Ca2 and Mg2 ions [4 to 6 mM and 2 to 4 mM, respectively] are not only expected to condense chromatin fibers but also should drive substantial fiber-fiber interactions. For this reason, when considering how chromatin could affect gene expression, one must consider that chromatin primarily exists in a highly ordered state in vivo. Reinforcing this point are elegant light and electron microscopy studies of mitotic and Interphase chromosomes. Fiber sizes ranging from 100 to 300 nm in diameter were observed throughout mitotic chromosomes, and electron micrographs of Interphase chromosomes also displayed a substantial amount of 100-nm-wide fibers. These very large fibers are unstable when nuclei are prepared in the absence of divalent cations or polyamines, mimicking the Mg2 dependence of folding and self-association seen for nucleosomal arrays in vitro.

What is the dynamic structural organization beyond the 30-nm fiber. But how do these structures influence gene function? Is transcription actually occurring on chromonema fibers, or are transcriptionally active regions less condensed? To answer these questions, Tumbar et al. used a mammalian cell line that contained a long, integrated array of LacI-binding sites. When imaged in living cells by decoration with a LacI-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein, this 90-Mbp tract appears as a single dot. In contrast, the foci decondensed when cells were transfected with an expression vector that produced a fusion of LacI-GFP to the VP16 transcriptional activation domain. The decondensed LacI tract appeared as an extended ribbon estimated to be 80 to 100 nm in diameter that coiled throughout a considerable volume of the nucleus. The 100-nm fiber colocalized with regions of bromodeoxyuridine-uradine 5′-phosphate incorporation, suggesting active transcription within the site, and recruitment of multiple HATs and increased histone acetylation were also observed. Thus, these data suggest that a 100-nm fiber may be the basic unit of higher order structure that is competent for gene expression. Because RNA polymerase II inhibitors did not block formation of the 100-nm fibers, the structural changes observed are not caused by transcriptional activity but more likely precede transcriptional activation at these sites. Fig. 2. Transcriptional activators induce large-scale changes in chromatin folding. (Left) DNA constructs containing LacI-binding sequences (orange boxes) upstream of a dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) gene (navy blue) were integrated into chromosomes as tandem ~90-Mbp arrays by Tumbar and co-workers. This locus can be visualized in vivo by expressing a LacI-GFP fusion protein (yellow-green protein), which images as a single green focus within the nucleus (top). In contrast, expression of a LacI-GFP-VP16 activator protein (yellow-green-red protein) produced a ribbon like chromonema fiber within a subset of cells (bottom). On the basis of comparison of ribbon length with the known base pair length of the DNA tract, fiber width was estimated at ~100 nm, which is considerably larger and more compact than even a fully condensed 30-nm nucleosomal array.

One concern with these studies is that these tandem LacI arrays are artificial and, thus, their behavior might be aberrant. To look in a more natural context, Mueller et al. examined the behavior of a tandem array of mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoters driving expression of a ras gene. Array structure and transcription were examined using a glucocorticoid receptor-GFP (GR-GFP) fusion protein to decorate the array in live cells and fluorescence in situ hybridization of fixed nuclei to verify transcription. The behavior of this MMTV array was dynamic. The addition of a GR agonist led to rapid (1 to 3 hours) decondensation of the arrays, with a rate that paralleled accumulation of ras mRNA. Even the decondensed, transcriptionally active arrays retained at least 50-fold more condensation than naked DNA, suggesting maintenance of at least a fully condensed 30-nm chromatin fiber. Therefore, both the LacI-GFP-VP16 activator and GR-GFP can drive local decondensation of a chromatin fiber. Because VP16 and GR are known to recruit either HATs or ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes, it is tempting to speculate that these activities play key roles in these decondensation events. In fact, the recruitment of transcriptional coactivators, including HATs and human SWI/SNF, was seen during MMTV array induction, and extensive histone acetylation accompanied VP16-dependent decondensation of the arrays examined by Tumbar et al..